The Poor Soul of Television

This is the second of two articles about public access cable television in New York. Part 1 can be found here.

By the late 1970s, Americans had reason to believe cable “narrowcasting” would totally eclipse, rather than just supplement, broadcast television. RCA launched its series of SATCOM satellites starting in 1975, which spawned a brood of national cable networks; HBO, TBS, TBN, ESPN, and CNN all debuted by 1980. On the ground, cable companies waged “franchise wars” to expand their territories into new market regions (or to conquer old ones where the original franchises had expired), competing in a battle of one-upmanship through mayoral bribery, grants for public programming, sparkling new public access facilities, and ever escalating guarantees of Tomorrowland delights.

Columbus, Dallas, Cincinnati, Houston, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and the suburbs of Chicago sold their streets to Warner-Amex for a glimpse of the marvelous QUBE, a modem-based two-way cable service. First installed in Columbus in 1977, QUBE expanded existing capacity to 40 or more channels, gathered ratings data of unprecedented accuracy, and established the prototypes for MTV, Nickelodeon, and The Movie Channel. More importantly, it came with a special remote with five extra signal-emitting buttons, which allowed the viewer to send signals back to QUBE headquarters. This made instant polling possible: each button was assigned a value at the programming source, in the form of a multiple-choice question, and the system immediately tallied and displayed the results. QUBE users could also order first-run pay-per-view movies and sports, video on demand, participate in onscreen auctions, and enroll in distance learning classes.

Manhattan, meanwhile, was saddled with a dated franchise, a measly 24 channels, and no interactive services. And yet, as ever, New York, the international epicenter of the stage, compensated for shoddy infrastructure with raw, live talent. The hams, showboats, and fourth-wall-breakers who flocked to cable access in the late 1970s didn’t need QUBE. Take the retired Broadway lyricist and composer John Wallowitch, host of John’s Cabaret, “the only piano bar of the airwaves.” As a phone number crawled across the bottom of the screen, Wallowitch, sitting at an upright piano, in evening dress and a bow tie, took requests over the air. He would perform whatever song his audiences wanted to hear, whether he knew the words or not. The show was surreal, but it was also truly interactive.

As New York Times critic John J. O’Connor pointed out in his 1982 review of a program called Tomorrow’s Television Tonight, live cable access was a throwback to the earliest days of television, when studios were cramped, cameras primitive, and the shows were live. “The constant teetering on the edge of chaos or, at the very least, a career-damaging flub, produced a special energy of its own, a tension that can rarely be duplicated on taped products.” Hosted by Soho Weekly News television critic Nicholas Yanni, Tomorrow’s Television Tonight appeared weekly on Channel D from 1978 until the host’s death in 1984. The show, O’Connor continued, “features a tiny stage, complete with rickety director chairs and, off to one side, a talented pianist who provides, in the manner of Academy Awards ceremonies, appropriate music for the introduction of each guest.” In one episode, the poker-faced host begins the show with an apology, “Tonight’s guests have not shown up.” From the tone of his voice and the blasé tinkling of ivory in the background, it is clear that this isn’t the first time. But the show must go on. Three or four friends, hanging around the studio, are immediately available for an interview.

Although TelePrompTer opened a live origination facility in 1973, New York's preeminent television critics did not cover any of the live programs from this part of the city (north of 86th Street), presumably because they lived further downtown, in the coverage area of Time-Life's subsidiary Manhattan Cable (MCTV). MCTV waited until 1976 to offer live airtime and studios (citing Anton Perich's "light bulb incident"—see Part 1—as a reason for holding out). On March 15, 1976, The New Yorker reported:

At 11:34 p.m. last Tuesday, Arnie Rosenthal's "The Big Giveaway," New York cable television's first game show, began live narrowcasting on public-leased Channel J from a Manhattan Cable TV studio on East Twenty-third Street to eighty thousand apartments and houses and eight thousand hotel rooms and a couple hundred bars on the southern half of Manhattan Island. "Giveaway's" gimmick: the contestants are the viewers, who phone in and answer questions and win prizes….Within seconds the phones were ringing, and a man named Corky won an Aqua-Vibrator Showerhead for correctly identifying Margaret Dumont as the woman who had the leading role in the most Marx Brothers pictures. A man named Fred answered the question with "Margaret Rutherford" and was awarded a consolation prize. So many people called up to answer the eight other questions…that the 260 telephone exchange was congested, and the telephone company estimates that at least five hundred calls failed to go through.

That tiny TV studio on East 23rd Street was called ETC Metro Access Studios. Although MCTV opened several live facilities in Manhattan, Metro Access was home to the most critically acclaimed (or at least critically acknowledged) cable access shows, including John’s Cabaret; Tomorrow's Television Tonight; If I Can’t Dance, You Can Keep Your Revolution; The Robin Byrd Show; Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party; The Vole Show; and The Live! Show.

In the world of television, call-ins were unique to public access. This marvelously simple conceit—combining live TV with phones—transformed the medium into something new: talk radio with a picture. Viewers could, for the first time, speak directly with the rabbis, psychics, and certified public accountants onscreen.

Some stars forged new genres. Robin Cohen, a stripper and porn star who had a role in Debbie Does Dallas, pioneered the phone sex show. She came to Channel J by way of Midnight Blue and started her own show, Hot Leggs, in 1977, which she later renamed after her stage alias, Robin Byrd. The Robin Byrd Show, one of the longest-running shows on public access, developed a cult following among straight and gay people alike who were mesmerized by her style and glamour; she posed in black crochet bikini beneath an iconic heart-shaped neon sign, and at the end of every show, she and her guests danced to her self-recorded theme song, “Baby, Let Me Bang Your Box.”

Along with dirty talk shows and quiz games, the "television party" format cropped up. These busy freeform soirées were more exciting than Anton Perich's Factory-clique tapes because they happened in real time, and invited viewers to join in over the phone. One of the earliest programs in this category was the yippee bonanza If I Can't Dance, You Can Keep Your Revolution (1977-95). Tobacco-brunette Coca Crystal danced, took phone calls, and conversed with an illustrious roster of guests, from a speech-slurring poet, to a man promoting canned wine, to Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs, Tiny Tim, Dame Edna, Debbie Harry, Chris Stein, and Philip Glass. David Letterman referenced Coca Crystal on The Late Show more than once. A typical episode features Coca, sitting in a folding chair and smoking a joint while someone behind her holds up a sheet with the show’s rather long name printed on it. (Evidently no thumbtacks were available, which makes one wonder how Robin Byrd managed to install her neon sign in the same space.)

The Vole Show was (and still is) a party with puppets. William Hohauser, then a young Metro Access employee, started the show in 1977, along with several teenage friends and a hysterical coterie of plush, musically inclined animals: Rapid T. Rabbit, a few frogs, and an unidentifiable creature with a saxophone snout. A typical segment might involve Styrofoam containers flying at the host’s head, puppets upending a card table, a reading from “Hitler’s recently excavated diary,” loud crashes resounding from other parts of the studio, and Hohauser screaming, “TO STOP THE SHOW, SEND MONEY!”

In the summer of 1976, a group of artists threw a block party to celebrate the wiring of the first address south of Houston Street, 152 Wooster, the home of Argentinean-born artist Jaime Davidovich. This was also the inaugural event of Cable SoHo, a group of local institutions (including Anthology Film Archives, Global Village, Franklin Furnace, and the Kitchen) and individuals working toward the development of locally controlled, arts-oriented television programming. From the back of MCTV’s mobile-media van, the head of the company’s public access department delivered Cable SoHo’s press release in a live telecast. Davidovich, the group’s first programming director, conducted video interviews with people on the street: “What do you think about art on cable television?” One woman explained she’d enjoy looking at art TV, now that she owned a color set. A man in a cravat likened cable television to Off-Broadway theater, explaining, “people have an opportunity on cable to experiment and experience and do things they might not be able to do on television because it’s so controlled.” A younger man, possibly British, announced that he was sick of “murder mysteries, detective stories, and yuk-yuk comedies,” and was ready to see something different.

Davidovich grew up in Buenos Aires and moved to New York City in 1963. Throughout the '60s, he experimented with minimalist painting

(white and then black), installation art (with adhesive tape), and

graphic design (the first edition of Hunter S. Thomspon's first book,

Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle

Gangs, and a line of stationery products for the Fluxus Group including paper

with printed-in crumpling, wallpaper of Yoko Ono’s ass, and

surrealistic lobster bibs). He started working in video in the early '70s when Porta-paks

became commercially available. Davidovich, along with

Douglas Davis and a handful of other early video artists, questioned

the logic of museum and gallery presentation of videotape. Why should

video be confined to the lofty vitrine? Cable television offered a much wider audience, they argued, and people would probably be more comfortable looking at video art from home. Was TV not the most significant medium of the 20th century? Not TV equipment as sculpture. Not the monitor as a closed-circuit display for videotape. Television: the living, traveling transmission of the signal itself.

To further this idea, Davidovich started the Artists' Television Network (ATN) in 1977, a nonprofit organization with a mission to “encourage the dissemination of video art through a commercial broadcast medium” and explore ways of presenting regularly scheduled, entertaining, and interactive programs on cable. With funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council on the Arts, the first enterprise of the Network was SoHo TV, broadcast on MCTV’s flagship station Channel 10 between 1976 and 1983. SoHo TV was a weekly arts magazine that featured interviews with John Cage, Vito Acconci, Les Levine, Dennis Oppenheim, Cindy Sherman, and others, and showcased their performance and video works. As the producer of SoHo TV, Davidovich infused the show with his brand of self-parodying humor, from the bombastic advertising spots to the frequently satirical tone of the interviews.

In December 1979, under the auspices of the ATN, Davidovich launched his own program on Channel J, the crown jewel of New York cable access: The Live! Show. Billed as "the variety show of the avant-garde," it combined skits, call-ins, interviews, opinions, music performances,

cartoons, and commercials in a whirlwind half hour of interactive entertainment. Many of his guests were comically gifted performance artists who

appeared in character, such as Michael Smith's “Mike” and Paul

McMahon's “Rock and Roll

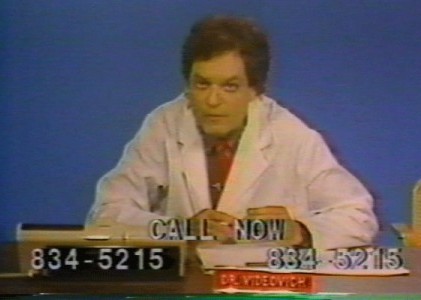

Psychiatrist.” Likewise, Davidovich frequently appeared as his alter

ego, “Dr.

Videovich of Buenos Aires, Specialist in Television Therapy.” Sitting behind a desk in a lab coat, Dr. Videovich offered live clinical consultation to people who suffered from TV addiction, improvising strange answers and deftly handling prank calls:

Caller: I watch too much TV. What can I do?

Dr. Videovich: After you watch two hours [of] TV, cover the TV with a plastic sheet. Then you won’t be able to watch it at least for a while.

Caller: Why do you look like a funky fucking lunatic?

Videovich, after hanging up: Ladies and gentlemen, this patient has a problem with television. But this is a family show. This man should come to talk to me in my office.

Wearing a beret, the doctor conducted art lessons (“How to Draw a Peaceful Scene From Latin America,” “How to Paint on Velvet”) and, in a belted trenchcoat, presented “man-on-the-street” investigative reports about his travels throughout he country. In “The Gap,” Videovich mistakes a mall in Long Beach for a contemporary art museum. “Saludos Amigos!” is a documentary about Lubbock, Texas, where the denim-suited doctor chases armadillos and discusses television, race and the Vietnam War with Christopher B. “Stubbs” Stubblefield, founder of the legendary Texan BBQ establishment-cum-music-venue. A tall man, Davidovich cut a conspicuous figure. Due to his formality and his accent, his interviewees regularly mistook him for a correspondent from a third-world TV station and acted like American ambassadors for his benefit. Sometimes he deliberately posed as a member of the press. Infiltrating

a press conference in Texas, Dr. Videovich asked Bob Hope his opinion on

Nam

June Paik and the future of video art. "Well, I'd like to see that.

Because I'd like to be part of the future." (The difference between Borat or Brüno and Dr. Videovich is that Sacha Baron Cohen’s characters are fictional. Dr. Videovich is an exaggeration of Davidovich’s innate identity. John J. O’Connor pegged the character as a mix of Bela Lugosi and Andy Kaufman, and indeed his persona is like that of Kaufman’s “Foreign Man,” except Davidovich is actually foreign. The accent is real.)

One of the live segments of the show was “The Video Shop,” where Videovich sold his collection of “Videokitsch,” describing the exact dimensions and many uses of TV-related items: a TV savings bank, Dukes of Hazzard TV tray, TV sunglasses, and a Winky Dink Interactive Television Kit in its original packaging. (Winky Dink and You was a CBS cartoon from the 1950s. The kit, sold by mail, included a plastic cover for the TV screen, used to decode secret messages and special markers for drawing on the screen to rescue the character from danger, such as drawing a bridge, at Winky Dink’s pleading, when he reached a raging river.) During the “Video Shop” segment, a phone number flashed, along with “ONLY $49.95! CALL OR SEND YOUR CHECK OR MONEY ORDER NOW!” Mixed in with the thrift-store finds were unique objets d'art, such as a ceramic TV cookie jar and a cardboard Christmas tree ornament depicting a televised Yule log, which Davidovich had personally designed and ordered for manufacture in Taiwan.

Also for sale in the video shop was a walking wind-up toy. Davidovich created a cartoon (actually more of a video comic strip, interspersing still drawings with text) around this item, “Tee Vee, the Poor Soul of Television.” Tee Vee, an adorably over-sensitive television set, slightly jealous of other appliances, longed to be a dynamic part of the human family. The mascot of The Live! Show, Tee Vee was a sublime tribute to Ernie Kovacs.

1984 was a rough year for cable idealists. Davidovich pulled The Live! Show off the air and dismantled the ATN after MCTV doubled the price of airtime on Channel J. Grant funding for the arts plummeted that year as well, after Reagan’s re-election. As it turned out, the problem with live television as an artistic medium was that an artist couldn’t make money doing it. He had nothing to sell. Davidovich’s last cable hurrah was a trip to Ohio. From the QUBE studios in Columbus, he administered a poll with a touch of Peronist humor. “What do you think of SoHo TV?” he asked. The five answer choices were “I like it,” “I like it a lot,” “I like it quite a lot,” “I don’t dislike it,” and “It's not bad.”

The FCC put an end to the Franchise Wars with the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984. This bill virtually guaranteed franchise renewals and allowed the cable industry to set its own prices. Warner sobered up after American Express dissolved its partnership that same year. QUBE was a money pit. Two-way cable was far too expensive to maintain with the existing analog systems.

Cable programming became a one-way street. People subscribed not because they wished to interact with their TVs, but because they wanted more of what television had always offered: news, sports, weather, cartoons, movies, sitcom reruns, talk shows. The networks continued to broadcast over the air. Cable was an annex of the same old wasteland, now stretching halfway to the moon thanks to satellite.

In one of the great ironies of cable history, one of QUBE’s interactive features struck a major blow to cable access: the system’s ability to track ratings. In 1984, Warner-Amex Cable Communications published market research indicating that only a small fraction of cable viewers were actually watching public access, using this study as proof that the maintaining of public channels and facilities wasn’t worth the cost. In the true test of electronic democracy, public access lost the popular vote.

In another darkly karmic development, in 1991, Manhattan’s cable companies discontinued the ribald Channel J and replaced it with C-SPAN. The golden age of public access in New York—the technical novelty, the democratic dream—was over. And yet, public access continued apace on C and D, and flourished throughout the country for another decade, poor ratings be damned. The producers themselves aren’t bitter about the demise of Channel J or the rise of the Internet; quite the contrary. Today, Jaime Davidovich’s studio is crammed with HD projectors and flat screens, and he carries with him a tiny flash-drive camera with a miniature tripod wherever he goes. In 1989, the Museum of the Moving Image curated a retrospective of The Live! Show (the full catalogue can be downloaded here). A sweeping, as-yet-unannounced retrospective of Davidovich's career is in the planning stages at another major museum. William Hohauser still hosts The Vole Show on the Manhattan Neighborhood Network and Justin.tv. Coca Crystal, who lives upstate, has an excellent YouTube channel. During the course of my writing this article, at least five people have

told me of Ugly George sightings. Evidently the host of Channel J’s Ugly George Hour still prowls the daylit streets in costume.

The program guide from a 1982 issue of On Cable magazine is a compelling read. What secrets unfurled on Foot Talk With Dr. Barry Boyle, Saturdays at 9:30 p.m.? Who hosted Calling All Vampires (Saturdays, midnight)? Was anyone injured during the Rampaging Jubilee (Sundays, 11:30 p.m.)? And how did it feel to Paint Alone With Helen (Sundays. 10 p.m.)? As Tee Vee might tell us, some shows are best appreciated when left to the active imagination.

On Friday, June 26, at 7 p.m., Leah Churner and Rebecca Cleman will present a screening of selections from The Live! Show called “Dr. Videovich or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love TV” as part of Light Industry’s “Obvious Dimensions” program at X Initiative's No Soul for Sale: A Festival of Independents. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

The Poor Soul of Television

The Poor Soul of Television

KEYWORDS

television | Coca Crystal | Jaime Davidovich | Robin Byrd | video artist | New York | public access cable televisionRELATED ARTICLE

Out of the Vast Wasteland by Leah ChurnerUn-TV by Leah Churner

More: Article Archive

FURTHER RESEARCH

"Jaime Davidovich: The Live! Show" (Museum of the Moving Image retrospective catalogue, PDF)Guide to the Jaime Davidovich Collection (Fales Library and Special Collections)

THE AUTHOR

Leah Churner is a film/video archivist and curator. She curated the series "Hollywood Musicals of the 1970s and 1980s" at Anthology Film Archives.

More articles by Leah Churner