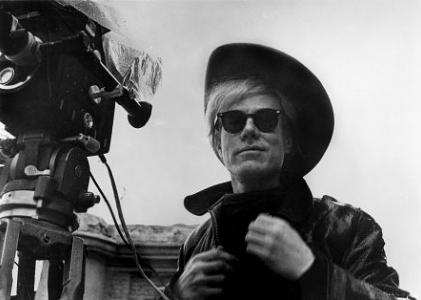

Spending Time With Andy

Warhol's World, Museum of the Moving Image, October 20-November 11, 2007

It's so easy to make movies. You just shoot and every time the picture comes out right. —Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol did little to promote the idea that he was a great filmmaker. He withdrew all his movies from circulation in the early 1970s, and later told an interviewer that he had no interest in releasing them on video: "The old stuff is better to talk about than to see. It always sounds better than it really is."

Indeed, Warhol's films (which were not re-released until after his death in 1987) have always been more talked about than seen. According to Archer Winsten's account in the New York Post, the 1964 premiere of his first film, a silent five-hour movie of the poet John Giorno sleeping, was attended by nine people, two of whom walked out in the first half-hour. "Is Andy Warhol really making movies, or is he playing a joke on us?" wondered Jonas Mekas, the Village Voice critic who was chronicling the emergence of the New York film underground.

Compared to the bohemian burlesque of the movement's cornerstone films—Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures, Ken Jacobs's Blonde Cobra, Ron Rice's Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man—that were screened regularly at The Film-Makers' Cooperative, where Warhol was a frequent audience member, Andy's movies appeared at first glance to be as unassuming as their titles: Sleep, Haircut #1, Kiss (all from 1963). Even the provocatively titled Blow Job (1964) presented itself as a conceptual joke, a continuous 35-minute shot of a man's face as all the "action" takes place offscreen.

Yet the first thing to say about Warhol's films is that they are not dry academic exercises. They are more experiential than intellectual, with incredible attention to human gesture and cinematic form. As soon as you adjust to the wry framing conceit of Blow Job, you realize that there is infinite nuance and interest in watching the subtlest changes in expression on actor DeVerne Bookwalter's face. Compiled from three-minute black-and-white silent film reels (the length determined by the capacity of Warhol's 16mm Bolex camera), Sleep, Haircut #1, and Kiss are exquisite visual studies of intimate human activities. The lighting, with painterly use of shadows, is delicate and moody. And while Warhol's camera is unblinking, it is never passive. As a cameraman, Warhol zooms and pans frequently, examining space and visually caressing his subjects. It is a fallacy to think of Warhol as a detached observer. Just the opposite; his unyielding gaze becomes a powerful form of direction—of both the actors and the audience. Warhol had the profound insight that the simple act of letting the camera run beyond the standard shot length can yield interesting behavior from the actors, and heightened attention and perception from the viewers.

The screen tests are the simplest demonstration of this; the subject—who could be anyone who walked into his studio—sat in front of the camera, which would run for three minutes. The natural narcissism and self-consciousness inspired by the setup would melt away as the camera ground on, giving way to vulnerability, honesty, and a sense of the real person behind the mask.

The screen tests were a daily activity, and feature-length films were produced almost every week during the staggering period of creativity in Warhol's white-hot artistic years from early 1963 through the spring of 1968, a period marked on one end by the revolutionary Pop Art gallery shows of his serial paintings of Elvis Presley, Jackie Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, and the Campbell's Soup cans, and on the other by his near-fatal shooting by Valerie Solanas in June 1968.

In this period, when he firmly established himself as not just the definitive postwar visual artist but also the key figure at the intersection of American art, celebrity, commerce, and popular culture, Warhol's films displayed astonishing variety and richness. What unifies them is a profound and original understanding that cinema is a medium of revelation, and that this revelation takes the form of human desire exposed over time and within carefully controlled space.

In early 1964, Warhol made two key moves that had enormous impact on his subsequent filmmaking. First, he opened his midtown studio, the Factory, which soon became a hub of both social and artistic activity as well as a makeshift soundstage and casting office. Secondly, he got a new camera, a 16mm Auricon that could record sound and could also hold thousand-foot film reels, allowing him to film continuously for more than half an hour.

With typically deceptive simplicity, Warhol said of his approach to directing, "I leave the camera running until it runs out of film because that way I can catch people being themselves." What this description purposely glosses over is the blend of artifice and reality, artistic control and passive observation, performance and candor that defined Warhol's cinema.

He created an entirely new form of filmmaking, with elements of fiction, documentary, home movie, and the avant-garde, but not subsumed by any one of these labels. It was as though he was making documentaries about real people who were acting as though they were performers in fictional films. "All my films are artificial," he once said. "But then everything is sort of artificial. I don't know where the artificial stops and the real begins."

While his subject may have been ordinary human behavior, his subjects were hardly ordinary humans. Perhaps compensating for his own shyness, Warhol was drawn to filming the outsize personalities for whom Jack Smith coined the label "superstars," including Gerard Malanga, Baby Jane Holzer, Mario Montez, Viva, Ondine, and his most incandescent star, the effervescent and completely enigmatic Edie Sedgwick. Warhol's films, despite their apolitical veneer, were documentaries of a vital and specific New York counterculture. Norman Mailer called Warhol's films historical documents and said, "A hundred years from now people will look at Kitchen (1965) and say, ‘Yes, that is the way it was in the late 1950s, early 1960s in America.'"

Despite their reputation, Warhol's films don't have a single boring moment. He would always start with a simple framework. In Harlot (1964), an homage to Jean Harlow, drag queen Mario Montez sits on a couch, eating banana after banana (inspiring a string of double entendres and bad puns), while a woman sits next to her stroking a kitten. Two men lounge behind them, gazing seductively into the camera. That's the movie. Yet the setup is fraught with sexual tension, and sex is always the underlying subject of Warhol's movies. If everything in Warhol becomes a metaphor for sex ("Oh, pulpy dreams of banana!..." exclaims Montez), then perhaps for Warhol, fimmaking itself was the grandest metaphor for this preoccupation. His other key preoccupation is death, that inevitable punctuation represented by the finite time of the film reel. Even the seemingly interminable Empire, an eight-hour view of the Empire State Building, has a beginning, middle—and end.

For Warhol, sex and death were flip sides of the same coin. His paintings and silkscreens of electric chairs, car crashes, gangster funerals, suicide leaps, and the recently deceased Marilyn Monroe and recently widowed Jackie Kennedy testify to his ongoing interest in morbidity. By its very nature, film is a time-based, ghostlike medium. One senses that Warhol was constantly recording and filming life as a means of defying death, and by extension, celebrating life.

Among Warhol's many great films is one clear masterpiece, Beauty #2 (1965), starring Edie Sedgwick. During the hour-long film, she lolls on a bed in her underwear, teasing and occasionally making out with the handsome, callow young Gino Piserchio. Offscreen right, her ex-boyfriend Chuck Wein questions and taunts her. Edie's pale skin is nearly washed out by a bright circle of white light in the center of the frame. She seems to be the source of this light; her energy—psychic, physical, emotional—radiates in different directions. Anger, impatience, physical attraction, amusement, arousal, boredom all seem to be occurring simultaneously. Wein's jealousy, condescension, and attraction to Edie are apparent, and the film's drama lies almost entirely in the juxtaposition between their emotional battle and the physical grappling that is taking place on the bed, all played out for the camera, and for us.

Andy, the bemused voyeur, silently controls the action. Far from passive, he is the creator of the sadistic yet compelling scenario. Edie somehow appears to have complete freedom and none at all. She is both object and subject, as dependent on us as we are on her. Warhol's films are filled with such power plays and alternations of perspective, which gives them a reflexivity and complexity worthy of Velázquez's Las Meninas.

Like the Velázquez painting, the films implicate and address the viewer. Warhol's films are always about their own filming. The signs of production are everywhere; actors talk to the writer and director; we see microphones in the frame; and often the films start with a crew member reading the names of director, writer, crew, and actors. Everyone—actors, crew, and viewers—is made aware that a movie is being made. The deal is that the camera won't stop rolling, and that something interesting must happen.

It is a daunting task to survey the variety and range of Warhol's films; Kitchen is an absurdist drama about a married couple, equal parts Beckett and Albee. Poor Little Rich Girl (1965) is nothing more—or less—than Edie Sedgwick going through her morning makeup routine, making some phone calls, and getting dressed; half the film out of focus, half in focus. Sunset (1966) is a delicate and gorgeous study of a series of sunsets at a Long Island beach. Since (1966) is a goofy, haphazard, and ultimately touching reenactment of the JFK and Lee Harvey Oswald murders.

The list goes on and on, and synopses do little justice because their basic situations are just starting points. Warhol virtually reinvented the entire history of cinema in five years, moving from short, silent, black-and-white movies to talkies to color to widescreen double-projector spectacles.

Warhol lost interest in filmmaking precisely as his films became commercial entities. The Chelsea Girls (1966) had a successful theatrical run, and starting around 1966, it was clear that there was a place for Warhol movies in the marketplace. Paul Morrissey become involved in their creation, first as a producer, and ultimately as the director of "Andy Warhol" films. Morrissey sought to make the films look more professional, and he added softcore and deliberately campy scenes to the mix. Morrissey's films did in fact reach a wider audience than Warhol's underground productions, but they were also of much less artistic value.

To see Warhol's films is to realize that they—even more than his canvases and silkscreens, which now command millions at auction—represent Warhol's greatest artistic accomplishment, the apotheosis of his many fascinations: with serial imagery, mechanical reproduction, celebrity, performance, spectacle, and the tension between pop culture and fine art. And with how we choose to fill our time. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Spending Time With Andy

Spending Time With Andy

RELATED CALENDAR ENTRY

Oct 20- Nov 11, 2007 Warhol's WorldMarch 31-April 8, 2007 The Real Edie Sedgwick

RELATED ARTICLE

Callie Angell (1948–2010) by David SchwartzNot Fade Away by Gregory Zinman

More: Article Archive

FURTHER READING

Andy Warhol: Senses of CinemaDecamping With Andy Warhol

Howard Hawks: Chicago Reader capsule reviews

THE AUTHOR

David Schwartz is the Chief Curator at the Museum of the Moving Image. He is also a Visiting Assistant Professor in Cinema Studies at Purchase College.

More articles by David Schwartz