Our Ancestors, the Gauls . . .

A People’s History in The Battle of Algiers

by Aaron Cutler and Mariana Shellard

posted July 6, 2012

We’ll

skip the formalities. You know why. The day will come when we will have

our weddings in the open. Remember we are at war against colonialism. A

strong army has occupied our country for 130 years. This is why the FLN

has to make decisions concerning the civil life of the Algerian people.

With this marriage we fulfill our duty, a duty of resistance.

— Wedding official in The Battle of Algiers

Algeria declared independence from France on July 2, 1962. Soon afterward Saadi Yacef left prison, where he had spent five years and avoided three death sentences for his role as a military head of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the major organization that had fought for independence. Yacef was determined to transform his book Memories of the Battle of Algiers, written while he was in prison and published that year, into a film that would popularize the history of the Algerian struggle for freedom. He went to Italy, the land of neorealism and home to Europe’s strongest film industry at the time, in search of a director. He met with Luchino Visconti, Francesco Rosi, and Gillo Pontecorvo, the last of whom had already spent several months in the city of Algiers researching the conflict. Pontecorvo told him that his treatment was naive. Yacef replied that Pontecorvo’s own planned project, Parà—the story of a paratrooper-turned-conscientious journalist (to be played by Paul Newman) reporting French torture of Algerians—would lack credibility, and might as well star John Wayne.

Yacef was born in 1928 in the Casbah, a poor, densely populated neighborhood of Algiers, where he grew up under a French system of apartheid. He was forced to end his formal education when the Allied forces turned his school into barracks during World War II. Three years later, in 1945, he joined a nationalist organization called the Algerian People’s Party (PPA) that supported Algeria’s independence movement. That same year a parade held by Algerians in the town of Sétif celebrating the end of the war and containing smaller anti-colonial demonstrations clashed with hostile French settlers, who tried to stop it. One hundred and three Europeans were killed, and many women raped; the offensives the French military launched in response slew anywhere between 1,020 and 45,000 Algerians, depending on the source. The massacre inspired Yacef first to join the PPA’s armed branch, then to join the FLN in 1954, nearly a decade later, at the start of the Algerian War of Independence. He fought until his arrest in 1957.

Pontecorvo, born in 1919 to a wealthy Jewish family, joined the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1941 and became a Resistance leader against Fascism. When he saw Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà (1946), made up of six episodes shot throughout a devastated Italy with nonprofessional actors, he was so enchanted by cinema’s ability to depict political realities that he began filming documentaries. He made his first fiction feature, The Wide Blue Road (1957), with the screenwriter and eventual longtime collaborator Franco Solinas, a year after breaking with the PCI over the organization’s support of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Road shows a fisherman (Yves Montand) corrupted by an unequal society that forces him to break the law in order to feed his family. Kapò (1959), Pontecorvo and Solinas’s next film, follows a Jewish teenager (Susan Strasberg) imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp as she takes on the task of policing other prisoners in order to survive.

Kapò’s most extreme violence is the annihilation of a person’s identity. Its protagonist oppresses others as a result of the greater oppression that has been inflicted on her. The receptive viewer understands her violence as a form of self-defense. Yacef had seen Kapò. With the Algerian film he wanted to ensure that the memory of a people who had been forced to learn their oppressor’s language, robbed of the right to publicly practice their religion, trapped within ghettos surrounded by barbed wire, and even killed wantonly by a foreign army would never be forgotten. He saw that Pontecorvo understood the need for violence in an independence movement, while Pontecorvo saw his own Italian Resistance struggles reflected in the Algerian fight. Their experiences were fundamental to each other.

Pontecorvo, Solinas, and Yacef began collaborating on a film about the rise and fall of the FLN’s fight between 1954 and 1957, including the period known as the Battle of Algiers. The film recreated many scenes from Yacef’s memoirs in their actual Casbah locations. The cast was composed of community members, including Yacef playing a version of himself. For the film to represent the people, the people would have to represent themselves. Ali la Pointe, a poor, illiterate boxer who became an iconic FLN leader and whose death temporarily forfeited victory to the French, was played by Brahim Haggiag, a poor, illiterate farmer. Other actors, found from among the Casbah’s 80,000 inhabitants in cafés and on the streets, gave face to their own histories regardless of their characters’ names. The idea of a “choral protagonist,” for which both Yacef and Pontecorvo would take credit, served an educative end. Its presence in the film certified the people’s participation in the War of Independence and preserved their memory for future generations.

France took over occupation of Algeria from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, but struggled to solidify its hold until four decades later, when an influx of settlers came as a result of loss of territory in the Franco-Prussian War. When the French arrived, around half of the native, predominantly Muslim population was literate, a higher percentage than in France, and Algerian children generally had access to formal education. By 1945, though, 1.25 million Algerian children had access to 699 primary schools, in contrast to the 1,400 schools available to 200,000 European children. More than 90 percent of Algerian children were illiterate in French. The rest studied under the French education system, whose history books often began with “Our ancestors, the Gauls…” The Algerians were not French citizens—they were colonial subjects.

Since Algeria was a French territory, the only possible full legal citizenship an Algerian could have was French. To become a French citizen, a Muslim Algerian needed to renounce Islamic law. The oppression and lack of representation gave birth to nationalist groups fighting for statehood. These organizations were frequently dissolved by the French military and then rebuilt by Algerian leaders. The efforts of the North African Star (ENA) led to resistance by, among others, the PPA, the Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties (MTLD), the Algerian Communist Party (PCA), and the FLN, which arose from a merger between several smaller groups. The FLN declared war against the French on All Saints’ Day of 1954.

***

— Wedding official in The Battle of Algiers

Algeria declared independence from France on July 2, 1962. Soon afterward Saadi Yacef left prison, where he had spent five years and avoided three death sentences for his role as a military head of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the major organization that had fought for independence. Yacef was determined to transform his book Memories of the Battle of Algiers, written while he was in prison and published that year, into a film that would popularize the history of the Algerian struggle for freedom. He went to Italy, the land of neorealism and home to Europe’s strongest film industry at the time, in search of a director. He met with Luchino Visconti, Francesco Rosi, and Gillo Pontecorvo, the last of whom had already spent several months in the city of Algiers researching the conflict. Pontecorvo told him that his treatment was naive. Yacef replied that Pontecorvo’s own planned project, Parà—the story of a paratrooper-turned-conscientious journalist (to be played by Paul Newman) reporting French torture of Algerians—would lack credibility, and might as well star John Wayne.

Yacef was born in 1928 in the Casbah, a poor, densely populated neighborhood of Algiers, where he grew up under a French system of apartheid. He was forced to end his formal education when the Allied forces turned his school into barracks during World War II. Three years later, in 1945, he joined a nationalist organization called the Algerian People’s Party (PPA) that supported Algeria’s independence movement. That same year a parade held by Algerians in the town of Sétif celebrating the end of the war and containing smaller anti-colonial demonstrations clashed with hostile French settlers, who tried to stop it. One hundred and three Europeans were killed, and many women raped; the offensives the French military launched in response slew anywhere between 1,020 and 45,000 Algerians, depending on the source. The massacre inspired Yacef first to join the PPA’s armed branch, then to join the FLN in 1954, nearly a decade later, at the start of the Algerian War of Independence. He fought until his arrest in 1957.

Pontecorvo, born in 1919 to a wealthy Jewish family, joined the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1941 and became a Resistance leader against Fascism. When he saw Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà (1946), made up of six episodes shot throughout a devastated Italy with nonprofessional actors, he was so enchanted by cinema’s ability to depict political realities that he began filming documentaries. He made his first fiction feature, The Wide Blue Road (1957), with the screenwriter and eventual longtime collaborator Franco Solinas, a year after breaking with the PCI over the organization’s support of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Road shows a fisherman (Yves Montand) corrupted by an unequal society that forces him to break the law in order to feed his family. Kapò (1959), Pontecorvo and Solinas’s next film, follows a Jewish teenager (Susan Strasberg) imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp as she takes on the task of policing other prisoners in order to survive.

Kapò’s most extreme violence is the annihilation of a person’s identity. Its protagonist oppresses others as a result of the greater oppression that has been inflicted on her. The receptive viewer understands her violence as a form of self-defense. Yacef had seen Kapò. With the Algerian film he wanted to ensure that the memory of a people who had been forced to learn their oppressor’s language, robbed of the right to publicly practice their religion, trapped within ghettos surrounded by barbed wire, and even killed wantonly by a foreign army would never be forgotten. He saw that Pontecorvo understood the need for violence in an independence movement, while Pontecorvo saw his own Italian Resistance struggles reflected in the Algerian fight. Their experiences were fundamental to each other.

Pontecorvo, Solinas, and Yacef began collaborating on a film about the rise and fall of the FLN’s fight between 1954 and 1957, including the period known as the Battle of Algiers. The film recreated many scenes from Yacef’s memoirs in their actual Casbah locations. The cast was composed of community members, including Yacef playing a version of himself. For the film to represent the people, the people would have to represent themselves. Ali la Pointe, a poor, illiterate boxer who became an iconic FLN leader and whose death temporarily forfeited victory to the French, was played by Brahim Haggiag, a poor, illiterate farmer. Other actors, found from among the Casbah’s 80,000 inhabitants in cafés and on the streets, gave face to their own histories regardless of their characters’ names. The idea of a “choral protagonist,” for which both Yacef and Pontecorvo would take credit, served an educative end. Its presence in the film certified the people’s participation in the War of Independence and preserved their memory for future generations.

France took over occupation of Algeria from the Ottoman Empire in 1830, but struggled to solidify its hold until four decades later, when an influx of settlers came as a result of loss of territory in the Franco-Prussian War. When the French arrived, around half of the native, predominantly Muslim population was literate, a higher percentage than in France, and Algerian children generally had access to formal education. By 1945, though, 1.25 million Algerian children had access to 699 primary schools, in contrast to the 1,400 schools available to 200,000 European children. More than 90 percent of Algerian children were illiterate in French. The rest studied under the French education system, whose history books often began with “Our ancestors, the Gauls…” The Algerians were not French citizens—they were colonial subjects.

Since Algeria was a French territory, the only possible full legal citizenship an Algerian could have was French. To become a French citizen, a Muslim Algerian needed to renounce Islamic law. The oppression and lack of representation gave birth to nationalist groups fighting for statehood. These organizations were frequently dissolved by the French military and then rebuilt by Algerian leaders. The efforts of the North African Star (ENA) led to resistance by, among others, the PPA, the Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties (MTLD), the Algerian Communist Party (PCA), and the FLN, which arose from a merger between several smaller groups. The FLN declared war against the French on All Saints’ Day of 1954.

***

The military machine was already in place. We had barely crossed the first terrace when a hail of bullets began raining down on us. Hassiba’s billowing pants were shot through several times, and I was wounded on my scalp. Ali and Dahmane, unharmed, went in the opposite direction. I later learned that Ali-la-Pointe had succeeded in breaking through the cordon and was crossing the streets of the Casbah, machine gun in hand, amidst the cheering of Algiers street urchins. Spontaneously, the children had the presence of mind to make themselves useful by serving as scouts for their heroes.

Hassiba and I remained in the cordoned area. Despite the rattle of exchanged gunfire, the terraces were overrun with women and children who, with great temerity, were witnessing what had become an almost daily show. I still wonder how the fighting stopped. I specifically remember the human belt forming a protective shield. From everywhere came cries, ululations, advice to show us the way to shelter from enemy fire. I remained immobile for a moment, as if hypnotized by the charm of this powerful demonstration of solidarity in action. Despite her insistence on sharing the same danger, I left Hassiba in the hands of friends.

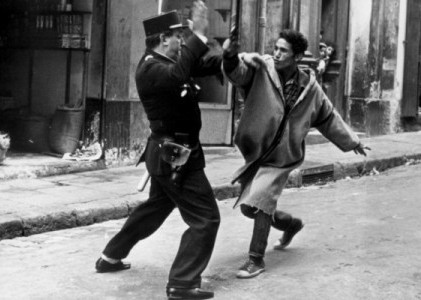

This account of the Algerian War of Independence, which lasted until 1962, comes from Yacef’s memoirs. The film The Battle of Algiers, completed in 1966 (and screening through July 12 at Film Forum in New York), enters the conflict through Ali la Pointe’s 1954 arrest for slugging a Frenchman and subsequent conversion to the FLN after witnessing the guillotining of an Algerian prisoner. Two years later, the increasingly influential organization moves to strengthen the Casbah by banning drugs, alcohol, and prostitution. A Muslim wedding, held in secret, becomes a communal act of protest. A coordinated wave of shootings of French police officers breaks out across the city. The French military surrounds the Muslim quarter with barbed wire and establishes identification checkpoints. The Algerian attacks continue. The French police commissioner plants a bomb inside the Casbah, destroying several homes and killing 75 people. As the Casbah cries “Murderers!” the FLN changes its strategy, targeting civilians with bombs planted throughout the European quarter. A French paratrooper division led by World War II and Indochina veteran Colonel Mathieu (Jean Martin) arrives to defeat the resistance. As the international media grows more involved in the Algerian issue, the United Nations meets to discuss it. The FLN declares a collective strike for Algerian workers in order to gain further attention. The paras storm the Casbah and break the strike. FLN bombing continues. The paras torture prisoners to learn their leaders’ whereabouts and capture or kill the FLN heads, culminating with the bombing of Ali la Pointe’s hideout. France wins the Battle of Algiers.

The film is structured around violence. Its first scene, showing an old Algerian man tortured and forced to wear a French uniform, defines the violence of colonialism as the attempt to annihilate the identity of the colonized. Each subsequent French offense is a continuation of this effort; each subsequent Algerian attack is its consequence. As stated by Frantz Fanon, the pro-FLN theorist whose book The Wretched of the Earth guided Pontecorvo and Solinas, “The symbols of society such as the police force, bugle calls in the barracks, military parades, and the flag flying aloft, serve not only as inhibitors but also stimulants. They do not signify: 'Stay where you are.' But rather ‘Get ready to do the right thing.’”

The colonized subjects do not fight for equality, but for existence, which means the indiscriminate recognition of civil rights. Violence is the result of a system that denies people these rights, the form the resistance of the oppressed takes against the oppressor’s efforts to keep them in place. Yet as the FLN leader Larbi Ben M’Hidi (actor's name unknown) tells Ali la Pointe in the film, “Acts of violence don’t win wars. Neither wars nor revolutions. Terrorism is useful as a start. But then, the people themselves must act.” The violence of the colonized serves as means to the end of individual autonomy by opening space for people to claim their rights. It is different in nature from the violence of the colonizer because its goal is not to replicate the colonial system, but to enable the colonized subjects to create their own system.

Independence began in 1962. FLN founding member Ahmed Ben Bella won an uncontested election to the office of president of the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria and ran a socialist government from 1963 to 1965, when his defense minister Houari Boumediène overthrew him in a military takeover. The FLN maintained one-party rule for nearly 30 years, during which the country’s economy grew greatly due to agricultural reform, industrialization, and oil nationalization, and its population more than doubled. The government built many primary schools and universities and increased the national literacy rate from less than 10 percent to over 60 percent. It also defeated several civilian demonstrations and mobilization efforts with military help, including the suppression of wide-scale protests in October 1988 that killed between 150 and 500 people.

The first open parliamentary elections, held in 1991, resulted in victory for the rival Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). The military then canceled the electoral process before FIS could take power and declared a state of emergency. President Chadli Bendjedid was forced out of office, and his successor, Mohamed Boudiaf, was assassinated. Around 200,000 people died over the next decade of civil war. Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the FLN-supported candidate elected president in 1999, gave amnesty to many members of the guerrilla movements, helping to diminish the conflict. Bouteflika was re-elected in 2004, and in 2006 his Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation, acknowledging and absolving many war crimes, entered law. He was elected a third time in 2009 (with the aid of a constitutional amendment allowing him a third term), and finally lifted the state of emergency last year in response to public protests over job and living conditions. His government has continually won elections amid high complaints of fraud, with more than 60 percent of the voting public boycotting this year’s parliamentary elections altogether. It has also maintained power by slicing the country's unemployment rate in half and giving citizens and small businesses easy access to government loans.

Algeria has been its own nation for 50 years now. During that time the nature of Western colonialism has changed from direct occupation to occupation by proxy, while still based on economic interest. Western Sahara is occupied by Morocco with French and Spanish support. Palestine is occupied by Israel with support from the European Union and from the United States. The overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, who improved Libya’s economy, literacy rate, and average life expectancy while in office without help from the International Monetary Fund, was supported by the United Nations. A flyer advertising a screening of The Battle of Algiers at the Pentagon in 2003, shortly before the invasion of Iraq that replaced its government with a U.S.-sponsored one, read, “Children shoot soldiers at point-blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar?”

The dichotomy between colonizer and colonized finds its contemporary mirror in the division between Western secular democracy and Islamic fundamentalism, the chief enemy in the war on terror. Yet perhaps Islamic law is actually a threat to Western democracy, as Communism was during the Cold War, because democracy does not see any other form of government as its moral equal. In The Battle of Algiers, Larbi Ben M’Hidi tells Ali la Pointe, “It’s hard enough to start a revolution, even harder to sustain it, and harder still to win it. But it’s only afterwards, once we’ve won, that the real difficulties begin.” His words still apply, half a century later, to an ongoing process. There’s still much work to do to achieve a decolonized world.

Pontecorvo died in 2006, having directed two fiction features about wars of decolonization after The Battle of Algiers. Yacef, still alive and a senator in Algeria’s Council of the Nation, regularly screens the film and leads discussions about Algerian independence with students in schools and universities.

Thanks to Péter Forgács, John Gianvito, Patrick Harrison, Rasha Salti, and Gary Crowdus and Cineaste Magazine

Sources:

The Battle of Algiers. Dir. Gillo Pontecorvo. Perf. Brahim Haggiag, Saadi Yacef, Jean Martin. Casbah Films & Igor Film, 1966. Both Criterion’s 2004 DVD and 2011 Blu-Ray release of the film contain a wealth of special features, including documentaries on the making of the film and the history of the Algerian War of Independence, as well as a filmed record of Pontecorvo’s return to Algeria in 1992.

The Battle of Algiers. Dir. Gillo Pontecorvo. Perf. Brahim Haggiag, Saadi Yacef, Jean Martin. Casbah Films & Igor Film, 1966. Both Criterion’s 2004 DVD and 2011 Blu-Ray release of the film contain a wealth of special features, including documentaries on the making of the film and the history of the Algerian War of Independence, as well as a filmed record of Pontecorvo’s return to Algeria in 1992.

Bignardi, Irene. “The Making of The Battle of Algiers.” Trans. Joanna Dezio. Cineaste: Vol. 25, No. 2, Spring 2000, p. 14-23.

Crowdus, Gary. “Terrorism and Torture in The Battle of Algiers: An Interview with Saadi Yacef.” Cineaste: Vol. 29, No. 3, Summer 2004, p. 30-37.

Esposito, Maria. “‘Stay Close to Reality.’” Interview with Pontecorvo. World Socialist

Web Site: June 9, 2004. Publisher International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI).

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Richard Philcox. 1961. New York:

Grove Press, 2005.

Forgacs, David. “Italians in Algiers.” Interventions: Vol. 9, Issue 3, November 2007, p. 350-364.

Gregory, Joseph R. “Ahmed Ben Bella, Revolutionary Who Led Algeria After

Independence, Dies at 93.” New York Times: April 12, 2012, p. A25.

Horne, Alistair. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. 1977. New York: New York Review Books, 2006.

Kaufman, Michael T. “The World; Film Studies; What Does the Pentagon See

in ‘Battle of Algiers’?”. New York Times: September 7, 2003.

Nossiter, Adam. “Algerians Belittle an Election, But Not Enough to Protest.” New York Times: May 19, 2012, p. A4.

Nossiter, Adam. “Algerian Election Results Draw Disbelief.” New York Times: May 12, 2012, p. A7.

Said, Edward. “The Dictatorship of Truth: An Interview with Gillo Pontecorvo.” Cineaste: Vol. 25, No. 2, Spring 2000, p. 24-25.

Sélavy, Virginie. “Interview with Saadi Yacef.” Electric Sheep: May 13, 2007.

Various. “Warscapes in Conversation with Saadi Yacef, October 2011.” Trans. Sara Hanaburgh. Warscapes: October 2011.

Yacef, Saadi. “The Battle of Algiers: A Memoir, Dec 1956-Sep 1957.” Trans. Ellen Sowchek. Warscapes: Nov 2, 2011.

Read Comments (0)

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

More

The Criterion Collection

The Battle of Algiers, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo

Photo Gallery:

Our Ancestors, the Gauls . . .

Our Ancestors, the Gauls . . .

Our Ancestors, the Gauls . . .

Our Ancestors, the Gauls . . .

Video:

The Battle of Algiers

The Battle of Algiers

The Battle of Algiers

The Battle of Algiers

KEYWORDS

The Battle of Algiers | film review | Saadi Yacef | Gillo Pontecorvo | Algerian War of Independence | political film | colonialism | violenceTHE AUTHORS

Aaron Cutler is a writer in São Paulo. His film writings can be found at http://aaroncutler.tumblr.com.

More articles by Aaron CutlerMariana Shellard is a Brazilian visual artist. Recent work can be seen at repartitura.com.

More articles by Mariana Shellard